Albert Einstein Is Labeled a Communist, Wins Nobel Prize in Nat Geo's 'Genius'

While Albert Einstein gets ready to flee Nazi Germany, he receives his first, long-overdue Nobel Prize in Chapter 8 of "Genius."

The famous Jewish physicist had been shunned by the scientific community for his controversial theories of relativity. In this episode, he seeks refugee status in the United States after the Nazi Party rises to power, just a few years before the start of World War II.

We're now one week away from the grand finale of this season of the scripted drama series, which airs Tuesdays at 9 p.m. on the National Geographic Channel. [The 'Genius' of Albert Einstein on Nat Geo Channel (Photos)]

In tonight's episode (June 13), Einstein (played by Geoffrey Rush) faces both good and bad news: He finally wins a long-anticipated Nobel Prize, but he also learns that his days may be numbered as he encounters some roadblocks while attempting to escape Nazi Germany.

Einstein wins the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics not for his theory of relativity, which was still considered controversial albeit arguably his most influential work yet. Instead, the Nobel committee gave him the prize "for his services to theoretical physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect."

With Einstein growing increasingly famous worldwide, the Nobel committee worried they were "beginning to look like fools" for not giving Einstein the prize, as the members discuss during tonight's episode. Still, they refused to give Einstein the prize for relativity.

While it's not quite what Einstein expected his first Nobel Prize to be for, the winning paper would not have existed had it not been for the work of Philipp Lenard. The anti-Semitic physicist had denounced Einstein's work as "Jewish physics" and called relativity a hoax. So Einstein seems pretty pleased with this sort of petty revenge; one of his biggest rivals is now partially responsible for Einstein's Nobel Prize.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

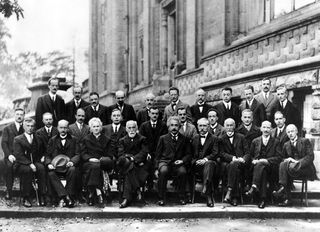

But the science certainly didn't stop with the new Nobel Prize. A few years later, Einstein began to debate quantum theory with atomic physicist Niels Bohr and theoretical physicist Werner Heisenberg, who is best known for his uncertainty principle. This idea states that it is impossible to measure a particle's position and momentum simultaneously to a certain degree of accuracy. Einstein felt that this notion in quantum mechanics didn't make sense, and he challenged other leading scientists to discuss the problem during the 1927 Solvay Conference on Electrons and Photons in Brussels, Belgium.

This Nobel Prize may have been one big win for Jewish scientists, but for Jews living in Europe at the time, things were starting to look very bleak. Nazis had started taking over Germany, and Einstein's name was on a hit list along with several other notable Jewish "enemies" of the German regime. Einstein and his wife, Elsa (Emily Watson), hoped to flee to the U.S. before the situation in Europe became too dangerous, but, as shown in this episode, they encounter some roadblocks while applying for a travel visa.

According to Raymond Geist, the U.S. Consul General in Berlin (played by Vincent Kartheiser of "Mad Men"), the American government has reason to believe Einstein is a member of the Communist Party and should therefore be denied an American passport visa. In a 16-page memo written to the U.S. State Department, Mrs. Randolph Frothingham, president of the Woman Patriot Corporation, accused Einstein of being a communist. She asserted that letting Einstein into the U.S. "would allow anarchy to stalk in unmolested."

The State Department took these accusations seriously. This was particularly true of J. Edgar Hoover, the director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) at the time. He took it upon himself to prove (with no success) that Einstein was indeed a communist.

Einstein eventually gained admittance into the U.S. to give a series of lectures at Columbia University and Princeton University. To find out how he made it into the country, you'll have to watch tonight's episode of "Genius" for yourself.

Email Hanneke Weitering at hweitering@space.com or follow her @hannekescience. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Hanneke Weitering is a multimedia journalist in the Pacific Northwest reporting on the future of aviation at FutureFlight.aero and Aviation International News and was previously the Editor for Spaceflight and Astronomy news here at Space.com. As an editor with over 10 years of experience in science journalism she has previously written for Scholastic Classroom Magazines, MedPage Today and The Joint Institute for Computational Sciences at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. After studying physics at the University of Tennessee in her hometown of Knoxville, she earned her graduate degree in Science, Health and Environmental Reporting (SHERP) from New York University. Hanneke joined the Space.com team in 2016 as a staff writer and producer, covering topics including spaceflight and astronomy. She currently lives in Seattle, home of the Space Needle, with her cat and two snakes. In her spare time, Hanneke enjoys exploring the Rocky Mountains, basking in nature and looking for dark skies to gaze at the cosmos.