The Universe is Dying? Now What?

Paul Sutter is a visiting scholar at The Ohio State University's Center for Cosmology and AstroParticle Physics (CCAPP). Sutter is also host of the podcasts Ask a Spaceman and RealSpace, and the YouTube series Space In Your Face. He contributed this article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Yes, the universe is dying. Get over it.

Well, let's back up. The universe, as defined as "everything there is, in total summation," isn't going anywhere anytime soon. Or ever. If the universe changes into something else far into the future, well then, that's just more universe, isn't it?

But all the stuff in the universe? That's a different story. When we're talking all that stuff, then yes, everything in the universe is dying, one miserable day at a time.

I mentioned in my last article (What Triggered the Big Bang?) how revolutionary the modern cosmological paradigm is: We don't live in a static, unchanging universe, but a dynamic one that has been around for a finite amount of time and will continue to change into its future. But what I didn't mention before is how agonizingly slow, painful and dreary the whole process will be.

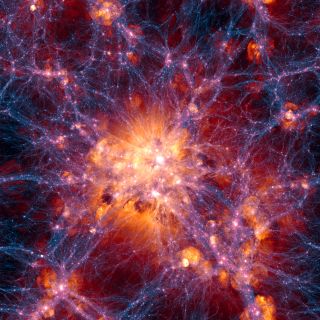

You may not realize it by looking at the night sky, but the ultimate darkness is already settling in. Stars first appeared on the cosmic stage rather early — more than 13 billion years ago; just a few hundred million years into this Great Play. But there's only so much stuff in the universe, and only so many opportunities to make balls of it dense enough to ignite nuclear fusion, creating the stars that fight against the relentless night.

The expansion of the universe dilutes everything in it, meaning there are fewer and fewer chances to make the nuclear magic happen. And around 10 billion years ago, the expansion reached a tipping point. The matter in the cosmos was spread too thin. The engines of creation shut off. The curtain was called: the epoch of peak star formation has already passed, and we are currently living in the wind-down stage. Stars are still born all the time, but the birth rate is dropping.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

At the same time, that dastardly dark energy is causing the expansion of the universe to accelerate, ripping galaxies away from each other faster than the speed of light (go ahead, say that this violates some law of physics, I dare you), drawing them out of the range of any possible contact — and eventually, visibility — with their neighbors. With the exception of the Andromeda Galaxy and a few pathetic hangers-on, no other galaxies will be visible. We'll become very lonely in our observable patch of the universe.

The infant universe was a creature of heat and light, but the cosmos of the ancient future will be a dim, cold animal.

The only consolation is the time scale involved. You thought 14 billion years was a long time? The numbers I'm going to present are ridiculous, even with exponential notation. You can't wrap your head around it. They're just ... big.

For starters, we have at least 2 trillion years until the last sun is born, but the smallest stars will continue to burn slow and steady for another 100 trillion years in a cosmic Children of Men. Our own sun will be long gone by then, heaving off its atmosphere within the next 5 billion years and charcoaling the Earth. Around the same time, the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies will collide, making a sorry mess of the local system.

At the end of this 100-trillion-year "stelliferous" era, the universe will only be left with the … well, leftovers: white dwarves (some cooled to black dwarves), neutron stars and black holes. Lots of black holes.

Welcome to the Degenerate Era, a state that is as sad as it sounds. But even that isn't the end game. Oh no, it gets worse. After countless gravitational interactions, planets will get ejected from their decaying systems and galaxies themselves will dissolve. Losing cohesion, our local patch of the universe will be a disheveled wreck of a place, with dim, dead stars scattered about randomly and black holes haunting the depths.

The early universe was a very strange place, and the late universe will be equally bizarre. Given enough time, things that seem impossible become commonplace, and objects that appear immutable … uh, mutate. Through a process called quantum tunneling, any solid object will slowly "leak" atoms, dissolving. Because of this, gone will be the white dwarves, the planets, the asteroids, the solid.

Even fundamental particles are not immune: given 10^34 years, the neutrons in neutron stars will break apart into their constituent particles. We don't yet know if the proton is stable, but if it isn't, it's only got 10^40 years before it meets its end.

With enough time (and trust me, we've got plenty of time), the universe will consist of nothing but light particles (electrons, neutrinos and their ilk), photons and black holes. The black holes themselves will probably dissolve via Hawking Radiation, briefly illuminating the impenetrable darkness as they decay.

After 10^100 years (but who's keeping track at this point?), nothing macroscopic remains. Just a weak soup of particles and photons, spread so thin that they hardly ever interact.

And then? Who knows? When you're contemplating such unfathomable time scales, it's hard to say. Maybe the universe will just continue cooling off, erasing temperature differences, making engines and computation — and cognition — effectively impossible.

But maybe our universe is just a small patch of a larger framework, and while our branch is dying, another piece of the greater cosmos is just now entering its glorious star-forming days. Not that you'll ever be able to reach it, but it's a small comfort. Maybe a chance fluctuation will ignite a new Big Bang. Maybe whatever's driving Dark Energy will reveal its true nature, decaying into a shower of matter, breathing fresh life into a broken-down cosmos. Maybe … maybe … maybe … Maybe not.

Have a nice day.

Learn more by listening to the episode "Is the universe dying?" on the Ask A Spaceman podcast, available on iTunes and on the Web at http://www.askaspaceman.com. Thanks to Alex Rothberg for the question that led to this piece! Ask your own question on Twitter using #AskASpaceman or by following Paul @PaulMattSutter and facebook.com/PaulMattSutter.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Paul M. Sutter is an astrophysicist at SUNY Stony Brook and the Flatiron Institute in New York City. Paul received his PhD in Physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2011, and spent three years at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, followed by a research fellowship in Trieste, Italy, His research focuses on many diverse topics, from the emptiest regions of the universe to the earliest moments of the Big Bang to the hunt for the first stars. As an "Agent to the Stars," Paul has passionately engaged the public in science outreach for several years. He is the host of the popular "Ask a Spaceman!" podcast, author of "Your Place in the Universe" and "How to Die in Space" and he frequently appears on TV — including on The Weather Channel, for which he serves as Official Space Specialist.