What's The Point? The Real Reason Scientists Study Space (Op-Ed)

Hannah Rae Kerner is chair of Students for the Exploration and Development of Space (SEDS), executive director of the Space Frontier Foundation, and a Ph.D. student at Arizona State University studying machine learning applications for astrophysics and robotic control. She contributed this article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Recently, my dad and I were in a Bojangles' restaurant in Charlotte, North Carolina. I grew up in that city, and I was visiting my family before starting graduate school in Tempe, Arizona. I was struggling to keep my egg and cheese biscuit together almost as much as I was struggling to answer my dad's question about what exactly I'd be doing in grad school. I explained for a while, my sentences peppered with words like "autonomous," "neural networks," "spectrometry" and "swarming." He listened and made a good attempt to understand, at least enough to relay the answer to others, and at the end delivered the inevitable, "Wow. That's really cool stuff." And then, "You know, all of that stuff is really cool and everyone working on it is supersmart, but I always kind of wonder what the point of it all is."

As the leader of two national space advocacy organizations, I should have been able to deliver a clear and confident answer. My dad's question was of the sort people in my field are asked all the time by the public and the media. But I stumbled. I rambled off some nonsense about how space research and technologies often result in useful medical and household technologies like MRIs, baby food and sneakers. To be honest, I always stumble on this question, probably because I'm never quite convinced by my own answer. Now I've realized why: It's not the right answer.

What's the point?

As space scientists, we're forced to explain how our work translates to people's daily lives, how we're helping them directly. In answering the question, "What's the point?", in converting the meaning of our work to units of impact on the average citizen, we are forced to dilute that meaning. In answering this question, we claim to be trying to put it "in layman's terms," but rather than teaching and fostering understanding, we are mutilating our work into some sort of "spin-off" explanation that feels like a lie.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The right answer is that thinking about problems on scales like the astronomical is good. It is fundamentally worthwhile for humans to push the boundaries of their understanding, to convert the unknown into the known through the power of scientific inquiry.

Rather than "What's the point?" the question should be, "What does thinking about and understanding these problems mean for humans and for the evolution of humanity as a part of the universe?"

Opening eyes

Scientific inquiry has led humans to discover that not just this planet but eight other planets (fine, seven other planets) orbit a star that is halfway through its lifetime. Humans discovered that at least one of those planets contains water and methane, because scientists built a robot, slingshot it across orbits that humans had discovered, and made it land itself on a planet 140 million miles 225 million kilometers) away and drill a hole, all by itself.

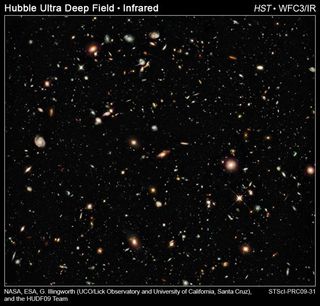

Astronomers took this image, a teeny-tiny sliver through the fabric of space-time, looking back more than 13 billion years:

Humans have not only walked on the moon, but also collected geological samples on it, tested theories of gravity on it and hit a golf ball on it. People took this picture of the Earth from the moon , showing humanity just how vulnerable this planet is, and inspiring its inhabitants to protect the only place in the universe known to harbor life:

Every one of those discoveries occurred because people were studying what inspired them, what they felt was worthwhile — what they loved to think about every day. What a backwards and miserable population humans would be if they could not work on the things that they love, that they feel are meaningful, that blow their minds. That people can hold an understanding, however tenuous, of something so large as the universe in something so small as the human brain makes this pursuit worthwhile.

The point of it all is that humans are seeking the point of it all.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.