Why Does Comet 67P Sing? Scientists Think They Know

The source of a strange "song" that was belted out by a comet as it hurtled through space may have finally been found.

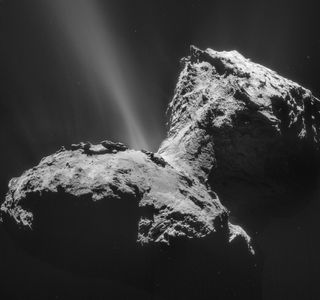

In August 2014, the European Space Agency's Rosetta probe picked up a ticking sound — like a long string of slowed-down, low-pitched dolphin clicks — coming from Comet 67P/ Churyumov-Gerasimenko during its journey toward the sun. The comet's song was unique compared with sounds picked up from other comets. Now, scientists think they know what's creating this space rock's uncommon crooning.

The sound waves picked up by Rosetta are moving through the comet's magnetic field. Scientists with the mission now say the vibrations are set off by a stream of charged particles ejected from the surface of the space rock, according to a statement from ESA. [Photos: Europe's Rosetta Comet Mission in Pictures]

Making sounds in space

In space, no one can hear you scream — that's because on Earth, sound waves move through the air, and there is no atmosphere in space. In empty space, there is no atmosphere, so the sound waves don't have a material to travel through. It's impossible for humans to hear sounds in the vacuum of space just like it's impossible to surf where there is no water — the waves need something to move through.

But last year, scientists recorded sounds coming from Comet 67P/C-G using the Rosetta Plasma Consortium (RPC) magnetometer instrument. This instrument measured the sound wave vibrations in the comet's magnetic field, according to a statement from ESA. Scientists with ESA transformed the magnetometer data into sounds that can human ears can hear, and the result is a strange clicking noise that changes in pitch and tempo.

Magnetic-field sound waves have been detected from other comets, including what may be the most famous comet of all, Comet Halley. But those comet songs display very different physical properties than the sounds measured at Comet 67P, and Rosetta scientists said those differences suggest an entirely separate mechanism is responsible for creating 67P's song.

So what causes Comet 67P's magnetic field to vibrate, generating this strange singing?

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The new research suggests the sounds are caused by a stream of charged particles (called plasma) that shoot off the comet's surface and interact with the magnetic field.

"The physical process is somewhat difficult to understand without a deeper understanding of plasma physics, but we can use a simple analogy to have a better idea of what's going on," Karl-Heinz Glassmeier, an author on the new paper, said in the statement. "Consider your garden hose. If you start the water flow, there is a chance that the hose starts to oscillate, generating waves. This is about what happens in the plasma. Of course, the flow we have in the cometary situation is not like water, but is a flow of charged particles. But somehow the analogy is suitable."

In Glassmeier's analogy, the hose is the magnetic field and the water is the stream of plasma. There is an additional step that is not contained in the analogy, and that is that the stream of plasma moves within the magnetic field in such a way as to create an unstable electric current. According to the statement from ESA, it is this current that ultimately exerts a force on the magnetic field, generating sound waves.

Singing the same tune?

The comet's song was first heard in August 2014, and could still be heard in February of this year, when the space rock was about 217 million miles (350 million kilometers) away from the sun, the statement said. The comet very recently reached perihelion — the point of its closest approach to the sun — and scientists observed a large amount of activity from the comet. Frozen material on the comet's surface turned into sprays of vapor, and boulder-size chunks of ice and rock were ejected into space, posing a potential threat to the Rosetta probe.

"Around this time, the activity [on the comet] is changing, other features show up, the plasma interaction region becomes much more violent," Glassmeier said in the statement. "Singing comet waves are still present, but buried under a variety of other features we are currently trying to understand."

The sounds heard from other comets, including Halley's famous comet, were also detected when those space rocks were closer to the sun than 67P was when its unique song was heard. Scientists now want to know whether 67P sings the same song as it nears the sun, or whether it changes its tune and emits the sounds detected from other comets.

"Whether we also observe the classical type of cometary waves, like those observed on Halley, is very difficult to judge," Glassmeier said in the statement. "We are heavily working on further analyzing the dynamics of this region to find out more."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter