'Venus Zone' Narrows Search for Habitable Exoplanets

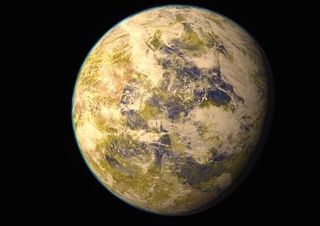

Long before the hunt began to find Earth lookalikes around other stars, one planet in the solar system had already been named Earth's twin.

With its similar size and mass, Venus measures very close to Earth, with one major yet significant difference: Its thick atmosphere makes temperatures on the planet hot enough to melt lead, and therefore most certainly too hot to sustain life.

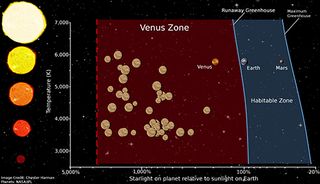

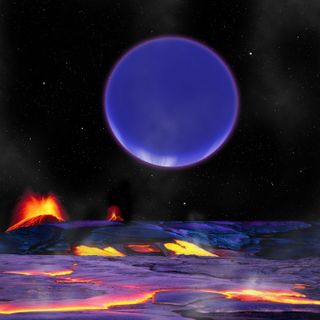

In order to weed out Venus-like planets from those that would be more habitable, several scientists, including planetary scientist Stephen Kaneof San Francisco State University, proposed the establishment of a "Venus zone" around stars, a region where the atmosphere could be consumed by a runaway greenhouse effect that superheats its planets. [Photos of Venus, the Mysterious Planet Next Door]

"We're specifically trying to make it clear that size is no indication of habitability," Kane told Astrobiology Magazine.

In other words, just because a planet is roughly the size of Earth, instead of, say, Jupiter, doesn't guarantee the conditions are right for life to evolve.

Defining the 'Venus zone'

The region around a star where liquid water can exist on a planet's surface is known as the habitable zone. But just because liquid water can exist doesn't mean that it does. Finding out the conditions on a planet often requires follow-up observations to initial discoveries, but limitations on observation time and equipment mean prioritizing which planets should be the first to be studied in-depth.

"The primary purpose of the habitable zone is target selection," said Kane.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Kane serves as the chair of NASA's Kepler Telescope's Habitable Zone working group, which seeks to utilize all available data from NASA's Kepler mission, along with any follow-up observations, to provide the most robust list of habitable-zone planets discovered by the telescope. The aim is to better understand how common Earth-size planets are in the habitable zones of other stars. To date, the telescope has identified more than 4,100 planetary candidates.

The Venus zone would similarly serve as a target-selection tool. Scientists hoping to find the next Earth-like planet perform follow-up searches on planetary candidates in the habitable zone; the establishment of a Venus zone would narrow down the inner edge of potential habitability.

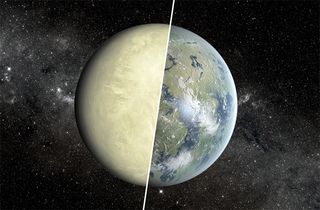

A planet within the Venus zone may form an ocean at some point in its history. Indeed, Venus is thought to have harbored wateron its surface until approximately one billion years ago, at which point it lost its liquid.

Kane and his team labeled the point at which a planet would lose its oceansdue to energy from its star as the outer edge of the Venus zone, and the inner boundary of the habitable zone. Losing liquid water would inhibit the carbon cycle of a planet, allowing more to build up in the atmosphere. Rising carbon levels would kick off a runaway greenhouse effect that would heat the planet.

The runaway greenhouse effect for a planet can be avoided if it experiences significant atmospheric loss. As the atmosphere escapes into space, it prevents the carbon from building up and superheating the planet. This loss of atmosphere establishes the inner edge of the Venus zone. [8 Ways Global Warming Is Already Changing the World]

Kane presented his research at the January meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Seattle. The work was also published in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Finding exo-Venus

The majority of the new planetary candidates discovered in recent years has come from NASA's Kepler telescope. Studying planetary atmospheres, however, continues to be a challenge, one that requires advanced telescopes and the right kind of stars. This situation may change in the future.

"At the moment, we lack enough planets around bright stars, and we lack the resources," Kane said. "Resources means James Webb."

Set to launch in 2018, NASA's James Webb Space Telescopewill be able to search for and study planets around distant stars. At the same time, the agenTransiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, or TESS, will map exoplanets around the brightest stars in the sky after its 2017 launch.

"James Webb combined with TESSwill really change the game," Kane said.

Because TESS searches for transiting planets — planets that are observed as they cross their star's face from the telescope's perspective — it will be more sensitive to those that orbit closer to their sun.

"TESS will see a lot more exo-Venuses than it will exo-Earths," planetary atmospheric scientist James Kasting, of Penn State University, told Astrobiology Magazine in an email. "These are the planets to rule out in the search of the more interesting exo-Earths."

At the same time, studying more exo-Venuses will help to narrow down the line between the Venus zone and the habitable zone, helping scientists to pinpoint which Earth-size planets are Earth twins, and which bear a stronger resemblance to Venus.

"Once we can observe these exo-Venuses and exo-Earths, we'll be able to determine more accurately the boundary between them," Kasting said. "Right now, that boundary is based entirely on theoretical climate models, which may not be very accurate under these distinctly non-Earth-like conditions."

Until then, scientists may have to deal with Venus twins posing as Earth analogues in the samples obtained by Kepler. Kane and his team identified 43 potential Venus analogs, and think that even more exist.

"I suspect a lot of Venus contamination in our sample," Kane said.

This story was provided by Astrobiology Magazine, a web-based publication sponsored by the NASA astrobiology program. Follow Space.com @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd