The scientists and engineers behind the most prolific planet-hunting mission in history have won the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum's highest group honor.

NASA's Kepler mission team will receive the museum's 2015 Trophy for Current Achievement during a ceremony in Washington, D.C. on Wednesday (March 25). Stamatios "Tom" Krimigis, head emeritus of the space department at Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Lab, will get the museum's Lifetime Achievement award at the same event.

"The winners of the 2015 Trophy Awards have significantly advanced space exploration and discovery in major ways," Gen. Jack Dailey, Director of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, said in a statement. "Few individuals have contributed more significantly to our knowledge of the solar system in a single career than Dr. Krimigis, and the Kepler Mission Team’s accomplishments have altered our views of possible life on other planets in our universe."

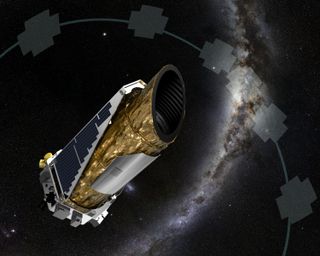

Since its March 2009 launch, the $600 million Kepler mission has discovered 1,019 exoplanets — more than half of all known worlds beyond our solar system. Kepler has also spotted more than 3,000 additional planet candidates that await confirmation; mission scientists estimate that about 90 percent of these will end up being bona fide planets.

Kepler's work has allowed scientists to determine that the Milky Way galaxy teems with tens of billions of planets, many of which are likely rocky worlds that lie in the "habitable zones" of their parent stars — that just-right range of distances where liquid water could exist.

Kepler detects planets by noticing the brightness dips caused when they pass in front of their host stars from the instrument's perspective. The spacecraft stared at more than 150,000 stars simultaneously during its original mission, which ended in May 2013 when the second of Kepler's four orientation-maintaining reaction wheels failed.

Krimigis, 76, has been a key player in space science and exploration for half a century. He has led or helped design experiments that have flown to all eight "official" planets in our solar system, and is participating in NASA's New Horizons mission to the dwarf planet Pluto as well.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.