In 'Five Billion Years of Solitude,' Author Lee Billings Searches for E.T.

NEW YORK -- For science writer Lee Billings, the search for alien life in the unvierse will reveal a lot about humanity.

In his book "Five Billion Years of Solitude: The Search for Life Among the Stars" (Current, 2013), which is now out in paperback, Billings dives headlong into the ongoing search for planets, and life, beyond our solar system, through in-depth interviews with some of the leading scientists in this field. And for Billings, the current discoveries are only the beginning. You can read an excerpt of his book here on Space.com.

We recently sat down with Billings here in New York City for a night of drinks and discussion about the search for another Earth, alien life and whatever else might be out there:

Space.com: Why did you write this book? What did you think needed to be said about the exoplanet hunt that hadn't been said by other books?

Lee Billings: First of all, I wrote the book because I was really tired of picking up books about exoplanets and the search for life, and it's always the same: there's a chapter at the very end, or there's five or 10 pages at the very end where the author says, "What about intelligent life? Maybe it's out there, maybe it's not. We're looking a little bit. Here's how we're kind of looking." And I just got so sick of that! That's not the end. That's the beginning! That's the whole basis for everything we're doing. I wanted to start with that. I wanted to set the stakes. Because that's what people really care about.

And the other thing was, I really wanted to connect the search for life and intelligence out there to the problems we're running into and the developments that we're seeing right here on Earth.

When you look out in space, anything you're going to be able to recognize as intelligence across interstellar distances is probably going to be more advanced than us. So by looking for these more advanced cosmic civilizations, we're trying to look, I think, for our own future. We're kind of trying to see what the possibilities are out there for a technological civilization or intelligent life that arises on a planet. What happens after that? Where are we going from here? I wanted to play with that notion and link it to trends that we see right now in our own society, on this one small planet. Trends like the accelerating pace of technological change and capability, as well as the accelerating pace of climate change, ecological degradation and biological destruction.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Space.com: Do you think there is life elsewhere in the universe?

Billings: Yeah, of course. The question isn't whether or not it's there; the question is how far away it is. Is the next mirror Earth, or something we would recognize as being inhabited, around the nearest star or within 10 light-years from here? Or is it in another galaxy on the other side of the universe?

Space.com: How do you think that question affects the search for exoplanets?

Billings: It affects it immensely. Depending on how frequent [Earth-like planets] are, that gives you an estimate of how far away the nearest one is. And that directly connects with how big of a telescope you would need to take their pictures, to study their atmospheres and surfaces for signs of life, and so on. So the question is really important for the field because the size of your telescope is obviously the main factor driving how expensive it is and how tough it is to build. [5 Exoplanets Most Likely to Host Alien Life]

Space.com: You talked to a lot of scientists looking for exoplanets; what are their hopes for the next 20 or 30 years for the field?

Billings: It's interesting to look at the spectrum of opinion that exists about where we should go in the future. Because there are a lot of different paths we could take.

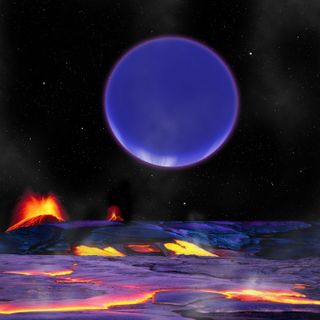

You have folks like David Charbonneau at Harvard, who makes the very reasonable, pragmatic argument that we should no longer pay much attention, in the near-term future anyway, to Earth-sun analogs, and we should instead focus the vast majority of our efforts on finding and studying super-Earths around M dwarfs.

[Editor's Note: Super-Earths are planets slightly larger than Earth but significantly smaller than gas giants like Neptune. M dwarf stars are significantly cooler and smaller than stars like our sun but are still hot enough to create habitable climates for orbiting planets. Super-Earths have been found in the habitable zones of their M dwarf stars (a region where the planet could have a surface temperature suitable for life).]

[Focusing on super-Earths around M dwarfs] makes a lot of sense from the viewpoint of having a flat or declining budget and just not being able to really push the envelope. It is easier to go out and study these systems. Finding and studying an Earth-twin around a sun-like star is much harder. So hard, in fact, that we haven’t done it yet. People forget in all the excitement over the recent explosion in exoplanet discovery rates that we still have not found any planet the size or mass of Earth in the habitable zone of a sun-like star.

All that said, I would bet against a strict focus on M dwarf super-Earths being a viable long-term strategy in the search for life beyond the solar system.

Space.com: Why would you bet against that? If M dwarf super-Earths are easier (hence, cheaper) to find, why not go after them as hard as we can?

Billings: I’m worried about the habitability of these planets, and I’m not alone in those worries.I'm not saying M dwarf super-Earths wouldn't be habitable, they just have a big unknown factor. We have no examples of super-Earths in our own solar system. We don't orbit an M dwarf. There are good reasons to think those planets have very different histories and environments than our own. So if your goal is to go find habitable planets, then to pin your hopes on this thing that's so different from your actual experience is pretty risky. Even though it's seen as the safe option because it's so easily achievable.

I think you could actually make the argument that it's riskier [compared] to an Earth-sized planet around a sun-like star, because we could easily have so much more trouble interpreting what we see, if we are fortunate enough to actually see [the super-Earth] atmospheres in the near future. [5 Bold Claims of Alien Life]

In one of the chapters of the book, I describe an important meeting that was organized by Sara Seager, a planetary scientist at MIT, called "The Next 40 Years of Exoplanets." At the meeting there was a great confrontation between David Charbonneau, who is all about M dwarf super-Earths and transit studies, and Geoff Marcy, who is kind of the dean of exoplanet detection and studies in America. Marcy said, 'No, we need to go for a bigger sample, we need to go for Earths around suns, we need to go for direct imaging, and we also need to do that with [technology] that ultimately give you the kind of high-resolution imagery that you need to answer important questions about a faraway planet's environment.' And so it's this great kind of tension. And I'm definitely more in that latter camp. I personally think it makes more sense [to look for Earth-sun analogs]. It also costs a lot more money. It's expensive. So you need more political weight to do that.

Space.com: I feel like the tone of the book is both very excited about what scientists are going to discover in the near future, but there's also feelings of frustration, and a fear that maybe the people asking the questions today won't be alive to learn the answers. Am I just focusing too much on the melancholy aspects?

Billings: No, that’s an accurate takeaway from the book. You have to remember, I started the project when the near-future of exoplanet studies was relatively bright, certainly brighter than it is right now. I began it back in 2007 before the financial collapse and the government bailouts and all that. People were still talking about launching a Terrestrial Planet Finder, a space telescope that could seek out and image Earths around a representative sample of nearby stars, sometime in the next decade or so, certainly in the 2020s. Now, no one at NASA really talks about doing that until sometime in the 2030s at the absolute earliest. The way things are going, this sort of thing could easily be deferred until the 2050s, or simply become nothing more than a frozen, half-remembered dream. Watching all that potential and momentum crumble and drain away was shocking and saddening.

But, you know, things are still very bright. The fact that the James Webb [Space Telescope] is going to be going up in 2018 and that we're going to try to use it to access and study the atmospheres of a handful of transiting M dwarf super-Earths is really, really exciting, and that's great.

I just think we should keep pushing and that we shouldn't settle. So as great as this amazing golden age is for all of astronomy, it could go away in the future without sustained support and public interest, and sound policy planning and execution. We need to keep pushing. We can't just settle for “good enough.” I think that this quest for extraterrestrial life, whether within or beyond the solar system, is so profound and exciting and important that it can actually sustain a lot of other investment and development in many other areas of space science. Because I feel like it's something that everyone has interest in.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter

Most Popular