Europe's Rosetta mission pulled off the first-ever soft landing on a comet Wednesday thanks to a lot of great engineering and hard work — along with a healthy dose of luck, mission scientists say.

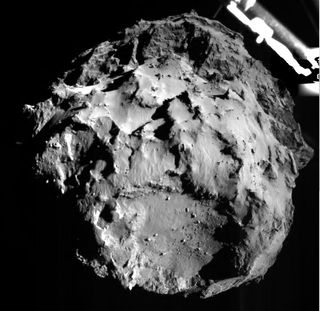

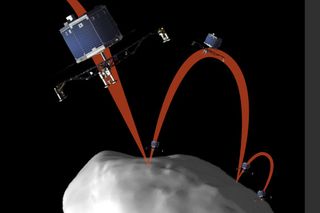

Rosetta's Philae lander successfully touched down on Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko early Wednesday morning (Nov. 12), more than 300 million miles (483 million kilometers) from Earth. But Philae's anchoring harpoons didn't fire as planned, and the 220-lb. (100 kilograms) probe bounced off the comet twice before settling onto its icy surface for good.

Philae survived the dramatic landing intact, however, and is already gathering a variety of data about the 2.5-mile-wide (4 km) Comet 67P. [Rosetta Comet Landing: Complete Coverage]

"We were very, very lucky yesterday — so much luck," Stephan Ulamec, Philae lander manager at the DLR German Aerospace Center, said during a news conference Thursday.

Bouncing off a comet

Philae's first bounce off 67P was a big one, sending the lander about 0.6 miles (1 kilometer) above the comet's surface, Ulamec said. Philae eventually came down again 1 hour and 50 minutes later, likely about 0.6 miles away from the original landing site. (The team still isn't sure exactly where the lander ended up.)

But the probe was nearly lost to space. It rebounded off 67P's surface at 0.85 mph (1.37 km/h); with a bounce of about 1 mph (1.6 km/h), Philae would have escaped the comet's minuscule gravity altogether, said Peter Schultz, a geoscientist at Brown University in Rhode Island. (Schultz has worked on three different NASA missions to comets and asteroids but is not part of the Rosetta team.)

To put those numbers in perspective: The escape velocity at Earth's surface is about 25,000 mph (40,230 km/h).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The second bounce lasted just 7 minutes and featured a rebound speed of 0.067 mph (0.11 km/h), Ulamec said. When it was over, Philae was oriented nearly vertically on the comet's surface, with one of its three landing legs apparently dangling into empty space. But the probe came through its ordeal in good shape and ready to collect data, which surprised Schultz. [Best Close Encounters of the Comet Kind]

"I'm actually flabbergasted," he told Space.com. "Somehow, the German gods were looking [over the mission]."

Good engineering certainly helped as well. As Philae spiraled down toward the comet, it did have enough kinetic energy to escape back into space, said Mark Hofstadter, deputy principal investigator for MIRO (Microwave Instrument on the Rosetta Orbiter). However, shock absorbers in Philae's legs absorbed and converted to heat much of that energy when the probe hit the surface the first time, he noted.

"Plus, a little energy was absorbed by the surface the lander hit (maybe crushing some rocks)," Hofstadter, who's based at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, told Space.com via email. "So knowing that even a tiny amount of energy was dissipated means that the lander would not have enough energy to escape again."

Indeed, the Philae team built some redundancy into the lander, allowing it to cope with a variety of different situations and parameters on Comet 67P, Ulamec said.

"The harpoons did not work, but the landing gear worked very nicely," he said.

And Schultz was quick to praise the Rosetta team and its multiple accomplishments. (This past August, the Rosetta mothership caught 67P after a 10-year chase and became the first spacecraft ever to enter orbit around a comet.)

Schultz observed that the Rosetta mission was conceived and developed more than 20 years ago, when researchers knew far less about comets than they do today.

"It's remarkable that this has worked so well," he said. "And this is why it's always worth it to dare, and to explore. That's the big lesson for me."

Lots of science to come

With the probe in its current precarious position, the mission team is hesistant to try firing the anchoring harpoons again or use Philae's drilling instrument, which can collect samples from more than 8 inches (20 centimeters) beneath the comet's surface, Ulamec said.

But Philae is already well into its "first science sequence" phase, or FSS, using its 10 different instruments to get a first taste of the comet. The FSS will last until Philae's primary batteries run out — perhaps two to three days after touchdown, mission officials have said.

The plan also calls for Philae to keep studying Comet 67P over the long term, using batteries that will be recharged by solar cells aboard the lander. This second phase was envisioned to last a maximum of three months or so, but expectations may have to be recalibrated downward after the double-bounce landing; Philae is only getting about 1.5 hours of sunlight per day in its current location, while the intended landing site offered 6 to 7 hours per day, the lander's handlers say.

Regardless, Philae should still manage to collect a great deal of interesting data, mission team members say. The lander's scientific gear is designed to study the composition and structure of Comet 67P in great detail. For example, one instrument employs radio waves to probe the interior of the comet's nucleus, while another identifies complex organic molecules on the surface.

"This is real comet geology now," Schultz said. "I think it's going to be a spectacular mission."

Comets are icy remnants left over from the solar system's formation 4.6 billion years ago, so observations made by Philae and the Rosetta mothership should shed light on the conditions prevalent when Earth and the other planets were taking shape, mission officials have said.

The Rosetta orbiter will continue studying Comet 67P through at least December 2015, observing how the comet changes as it gets closer and closer to the sun. (67P's closest approach will come in August 2015, when it zooms within 1.25 Earth-sun distances of our star.)

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.