Exoplanet hunters have just made it easier to identify alien Venuses, in the hopes that doing so will lead to the discovery of more alien Earths.

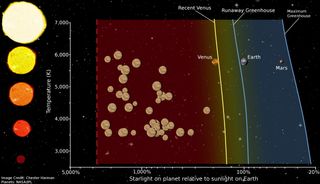

A team of researchers has delineated the "Venus Zone," the range of distances from a host star where planets are likely to resemble Earth's similarly sized sister world, which has been rendered unlivably hot due to a runaway greenhouse effect.

The new study should help scientists get a better handle on how many of the rocky planets spotted by NASA's prolific Kepler space telescope are truly Earth-like, team members said. [Gallery: A World of Kepler Planets]

"The Earth is Dr. Jekyll, and Venus is Mr. Hyde, and you can't distinguish between the two based only on size," lead author Stephen Kane, of San Francisco State University, said in a statement. "So the question then is, how do you define those differences, and how many 'Venuses' is Kepler actually finding?"

The results could also lead to a better understanding of Earth's history, Kane added.

"We believe the Earth and Venus had similar starts in terms of their atmospheric evolution," he said. "Something changed at one point, and the obvious difference between the two is proximity to the sun."

Kane and his team defined the Venus Zone based on solar flux — the amount of stellar energy that orbiting planets receive. The outer edge of the zone is the point at which a runaway greenhouse effect would take hold, with a planet's temperature soaring thanks to heat-trapping gases in its atmosphere. The inner boundary, meanwhile, is the distance at which stellar radiation would completely strip away a planet's air.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The thinking is similar to that behind the "habitable zone" — the just-right range of distances from a star at which liquid water, and perhaps life as we know it, may be able to exist.

The dimensions of these astronomical zones vary from star to star, since some stars are hotter than others. In our own solar system, the Venus Zone's outer boundary lies just inside the orbit of Earth, researchers said.

Future space-based instruments — such as NASA's $8.8 billion James Webb Space Telescope, scheduled to launch in 2018 — will be able to analyze some exoplanets' atmospheres, helping scientists refine the Venus Zone concept, researchers said.

"If we find all of these planets in the Venus Zone have a runaway greenhouse-gas effect, then we know that the distance a planet is from its star is a major determining factor. That's helpful to understanding the history between Venus and Earth," Kane said.

"This is ultimately about putting our solar system in context," he added. "We want to know if various aspects of our solar system are rare or common."

The telescope suffered a glitch in May 2013 that ended its original exoplanet hunt, but Kepler has embarked upon a new mission called K2, which calls for it to observe a range of cosmic objects and phenomena.

The new study has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.