To Restart Vintage NASA Probe, Private Team Turns to the 'Borg'

After sputtering to a stop during course corrections last week, the initial suspicion that a vintage spacecraft is out of gas might not be correct, says the co-leader for the International Sun-Earth Explorer (ISEE-3) Reboot Project. And they have a backup plan to move it today (July 16).

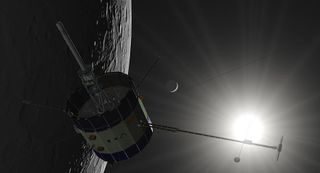

ISEE-3 is a 36-year-old NASA probe that Cowing's team took over a few weeks ago with aims to repurpose it for a citizen science project. The team's prime mission goal now is to maneuver the spacecraft into an orbit that will put it relatively close to Earth.

Hopes of that briefly faded last week, however, when during the second of several "burns" July 10 the engine for ISEE-3 didn't produce acceleration. While the spacecraft was healthy, the group said on its Twitter feed and website that it appeared to be out of gas. [See images of the ISEE-3 spacecraft]

Further investigation showed that conclusion could be wrong, Cowing told Space.com. After crowdsourcing and consulting with propulsion experts, his team thinks it might be because hydrazine gas in the tanks broke down over the decades into "decomposition products" that are blocking the line.

"What we're going to try and do this time is heat the tanks up a bit more than we have been, and open some valves internally and let gases flush out," he said.

"When that happens, we turn the engine on and fire several hundred pulses, clean the engine out and somewhere in that process hopefully see acceleration."

'We Are Borg'

In a blog post on the ISEE-3 Reboot Project website, co-leader Dennis Wingo described the "Borg" mind of volunteers worldwide who chipped in their ideas when the team put out a call for help. ("Borg" refers to an alien species in Star Trek that assimilated others into a collective.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Unlike most failure investigations in NASA and other entities, the team had few resources or outside expertise to draw upon, Wingo wrote in the post, partly titled "We Are Borg".

"No one on our team is an experienced hydrazine expert," he said. "After receiving a few e-mails from people who offered suggestions on what might have happened, [we] decided to throw the problem out to the world. I was astonished at the response."

The July 10 post on the ISEE-3 blog and NASA Watch (Cowing's website) generated many suggestions, including some from "the most qualified professionals in the world," Wingo said, while declining to name names due to privacy concerns.

Through a combination of inadvertent procedural errors (because the spacecraft documentation was incomplete) and physics, the collective narrowed in what might have caused the problem: the hydrazine decomposition products, and possible spacecraft mechanical troubles as well.

"High temperatures expanding the seal material could have either impeded the flow, or have precluded the latch valve from opening even with the microswitch indicated to telemetry that the valve was open," Wingo wrote. "We also have high temperatures possibly … causing a large gas bubble in the propellant lines."

Working down the fault tree

The test of this will likely come during a series of maneuvers today (July 16), when controllers talk to the spacecraft through the powerful Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico.

Cowing said the three-hour window, which opens around 12 p.m. EDT (1600 GMT), will be a matter of working down the "fault tree." Controllers have a sequence in mind, and if the sequence doesn't work they have a series of backups available that they will run through. This process could even take several days, he added.

"It involves the fact that the spacecraft does have a redundant propulsion system, A and B side, and you can cross-connect between them. There are several pairs of engines that you can use."

If the spacecraft does accelerate as controllers hope, Cowing said they would still have several weeks to maneuver the spacecraft as they originally planned. That opportunity begins to close in late July when the fuel demands become greater.

He estimated that this course correction would take maneuvers equaling 10 meters (32.8 feet) per second. The spacecraft has an estimated 130 to 140 meters (427 feet to 460 feet) per second of propellant left in its tanks, some of which would be needed to further refine the orbit.

"We'll swing around the moon, fire again, and do some more trim burns. It's a safe margin. We're assuming all the fuel that should be in there based on what was launched in the spacecraft and what was used historically," Cowing said.

Plan B

Cowing emphasized the spacecraft isn't "lost" if these maneuvers don't pan out. Even if the spacecraft's trajectory can't be corrected, he said it will be possible for smaller dishes to listen to ISEE-3 indefinitely as it wanders through the inner solar system. Science will still happen, but just from a different location than planned.

His group includes a science team that is examining the 13 science instruments to see which ones work. The magnetometer so far is confirmed to be just fine, sending back data on a solar event that happened a short while ago.

"Contrary to all this doom and gloom that we have lost it, we are in command of it now," said Cowing.

The team is prepared to adapt the mission according to what the spacecraft is capable of, he added. For example: if the propulsion system isn't able to be fixed, they may turn off the heaters and save the power for other instruments.

And engineering data is already yielding some surprises. The solar panels are healthier than what was expected, working at levels that were supposed to be possible only at the five-year mark in the mission, Cowing said. This information could be used, he said, for future spacecraft designs as NASA seeks to explore the inner solar system.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or Space.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022 covering diversity, education and gaming as well. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before joining full-time. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House and Office of the Vice-President of the United States, an exclusive conversation with aspiring space tourist (and NSYNC bassist) Lance Bass, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?", is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams. Elizabeth holds a Ph.D. and M.Sc. in Space Studies from the University of North Dakota, a Bachelor of Journalism from Canada's Carleton University and a Bachelor of History from Canada's Athabasca University. Elizabeth is also a post-secondary instructor in communications and science at several institutions since 2015; her experience includes developing and teaching an astronomy course at Canada's Algonquin College (with Indigenous content as well) to more than 1,000 students since 2020. Elizabeth first got interested in space after watching the movie Apollo 13 in 1996, and still wants to be an astronaut someday. Mastodon: https://qoto.org/@howellspace

Most Popular