Alien Planet Camera Is Most Sensitive Exoplanet Imager Yet

A newly christened telescope imager built to snap photos of alien planets around distant stars is the most sensitive camera of its kind, preliminary tests show.

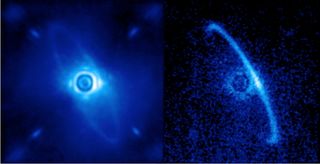

The Gemini Planet Imager (GPI), installed on the Gemini South telescope in Chile, is dedicated to directly imaging exoplanets. Every aspect of the device is tuned for maximum sensitivity to faint planets near bright stars, according to scientists using the instrument.

The imager is armed with a sophisticated "adaptive optics" system that actively corrects for the blurring effects of Earth's atmosphere. It also possesses a coronagraph that blocks starlight so planets can be seen. [7 Ways to Discover Alien Planets]

New eyes on alien planets

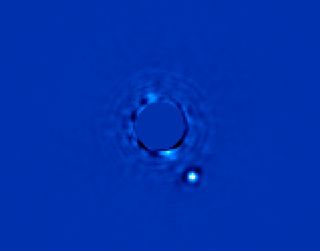

Earlier this year, in January, scientists unveiled the "first light" photo of an alien planet observed using GPI. Though released on Jan. 7, the image was taken on Nov. 11, 2013, while scientists aimed the GPI camera and telescope at the exoplanet Beta Pictoris b.

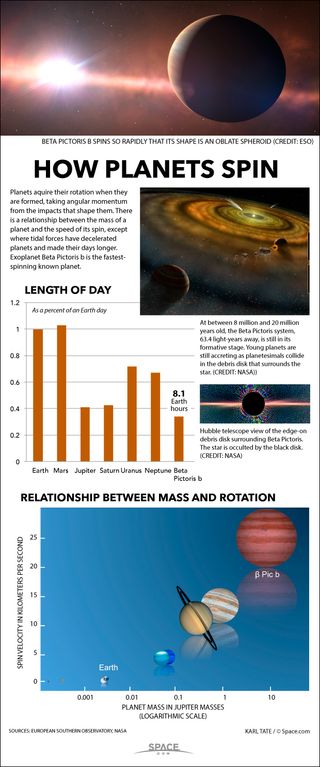

GPI's first target was a known planet located 63 light-years from Earth, around the star Beta Pictoris, the second brightest star in the southern constellation Pictor, the Easel. Discovered in 2008, Beta Pictoris b is a gas giant about two-thirds wider than Jupiter and 3,000 times more massive than Earth, and scientists recently measured the length of Beta Pictoris b's day, the first time researchers have clocked the day on a planet in another solar system.

Imaging planets is extremely challenging — for instance, Jupiter is a billion times fainter than the sun in reflected visible light. These new findings revealed GPI has improved the contrast of planetary imaging about 50-fold.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The imager detected Beta Pictoris b with just a single photo involving an exposure time of 60 seconds, with minimal image processing afterward. For comparison, previous efforts required more than an hour of exposure time, as well as significant image processing afterward.

"It's certainly exciting that GPI worked so well right out of the box," said lead study author Bruce Macintosh, an astronomer at Stanford University in California.

"When we took our very first image of a planet, it wasn't surprising that the planet was there — it had been seen long before — but that we could see it in a single, 1-minute image with no fancy processing, as opposed to an hour of telescope time and lots of advanced image processing [as was needed] with previous instruments, was amazing," Macintosh told Space.com. "Everyone in the control room was astounded and happy."

Exoplanet Beta Pictoris b in-depth

Using GPI, scientists discovered that Beta Pictoris b takes 20.5 years to orbit its star at a distance about nine times that of Earth from the sun, which is slightly closer than Saturn orbits the sun.

"We can see young systems like Beta Pictoris where planets are just barely done forming, so we can help fill in the early days of solar system evolution," Macintosh said. "Filling in these pieces of the planet distribution is important to constrain models of planet formation and tell how common systems like our own might be." [Alien Planet Beta Pictoris b in Pictures (Gallery)]

The researchers calculate the exoplanet has a 4-percent chance of transiting, or passing in front of, its star in late 2017. "If that happened, it would be amazing — no transiting planet has ever been directly imaged," Macintosh said. A transit measurement would let astronomers know exactly how wide Beta Pictoris b is, which in turn, combined with other details, can help verify its temperature and other aspects of the planet.

In addition, the GPI will analyze the compositions of the exoplanets it sees. Scientists can detect the makeup of a planet by using instruments known as spectrographs to look at a planet's light, which comes in a wide variety of wavelengths, some visible, many invisible. The spectrum or wavelengths of light that an element gives off can act like a fingerprint, revealing the identity of the material in question.

"Composition is a key window into atmospheric properties," Macintosh said. "For example, strong vertical winds in extrasolar planets destroy the methane that we had expected to find."

The researchers plan to spend a year or so tuning GPI and seeing how it performs. Then, in November, the scientists plan to use the imager to discover more exoplanets by scanning 600 young, nearby stars over the course of three to four years.

"Simulations say we should get 20 to 50 new imaged planets, a huge step forward," Macintosh said.

The scientists detailed their findings online May 12 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us