Apollo 1: A fatal fire

The Apollo program changed forever on Jan. 27, 1967, when a flash fire swept through the Apollo 1 command module during a launch rehearsal test. Despite the best efforts of the ground crew, the three men inside perished. It would take more than 18 months of delays and extensive redesigns before NASA sent any men into space.

NASA had a lofty goal, set by President John F. Kennedy in 1961, to land a man on the moon and return him safely to Earth by the end of the decade. Earlier Mercury and Gemini flights had been the first steps toward that goal, testing how humans behaved in space and how to do technical spacecraft procedures such as rendezvous. Now the Apollo missions would take astronauts all the way to the moon for orbital missions and landing missions. The first manned mission — an Earth-orbiting mission — was originally designated Apollo Saturn-204, or AS-204, but was later renamed Apollo 1.

The Apollo 1 fire was a difficult time for NASA and its astronauts, but the improvements in astronaut safety allowed the agency to complete the rest of the program with no further fatalities. The agency also met Kennedy's goal of landing a man on the moon in 1969, during Apollo 11.

NASA had a special ceremony honoring the Apollo 1 astronauts on the 50th anniversary of their deaths in 2017, which included unveiling a new exhibit at the Kennedy Space Center showing the hatches of the damaged command module.

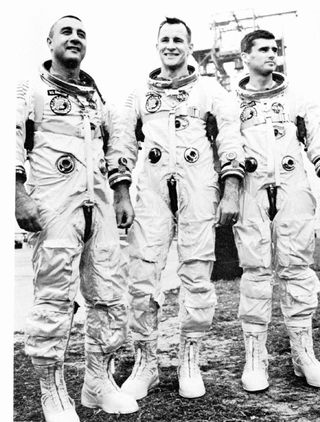

The astronauts

The Apollo 1 crew commander, Virgil "Gus" Grissom, was an Air Force veteran of the Korean War. He was chosen was among NASA's first group of seven astronauts, the Mercury Seven. Grissom was America's second person in space in 1961. On that mission, Mercury's Liberty Bell 7, the hatch door blew for unknown reasons upon splashdown. Grissom ended up in the water and was rescued by a helicopter (which at first tried, in vain, to pick up the spacecraft; the spacecraft was later pulled from the ocean floor in 1999).

Some in the Astronaut Office were skeptical that Grissom's reputation would recover (many believed Grissom blew the hatch; he swore he didn't). However, Grissom successfully commanded the first Gemini flight, Gemini 3, and was selected to do the same for Apollo.

Fellow spaceflight veteran Ed White, an Air Force lieutenant colonel, was the first American to make a spacewalk, on Gemini 4 in 1965. The images of him soaring in space for 23 minutes are still frequently seen today; it is considered one of history's most memorable spacewalks.

Roger Chaffee was a seasoned Navy lieutenant commander who joined the program in 1963. Although a rookie in space, he had spent years supporting the Gemini program, most publicly as CapCom on Gemini 4. Now getting a chance to fly after five years in the program, he said, "I think it will be a lot of fun."

Gone in an instant

Every astronaut in the Apollo program had flight experience, and many were test pilots. They were used to seeing machines under development and dealing with delays, and assessing the airplanes' readiness for flight. In the view of many of these astronauts, the Apollo command module just wasn't ready yet. Engineering changes were still in progress as NASA prepared for the countdown test.

On his last visit home in Texas, Jan. 22, 1967, Grissom grabbed a lemon off a citrus tree in the backyard. His wife, Betty, asked what he was going to do with it. "I'm going to hang it on that spacecraft," he answered as he kissed her goodbye. He hung it on the flight simulator after he arrived at the Cape.

The morning of the test, the crew suited up and detected a foul odor in the breathing oxygen, which took about an hour to fix. Then the communications system acted up. Shouting through the noise, Grissom vented: "How are we going to get to the moon if we can't talk between two or three buildings?"

With communications problems dragging on, the practice countdown was held. Then at 6:31 p.m. came a frightening word from the spacecraft: "Fire."

Deke Slayton, who oversaw crew selections at NASA and was present for the test, could see white flames in a closed-circuit television monitor pointing toward the spacecraft. The crew struggled to get out. Technicians raced to the scene, trying to fight the fire with extinguishers amid faulty breathing masks.

Video: Apollo 1 Remembered – Report from the Archives

At last, the door was open, but it was too late.

The aftermath and changes

A NASA review board found a stray spark (probably from damaged wires near Grissom's couch) started the fire in the pure oxygen environment. Fed by flammable features such as nylon netting and foam pads, the blaze quickly spread. [Infographic: How the Apollo 1 Fire Happened]

Further, the hatch door — intended to keep the astronauts and the atmosphere securely inside the spacecraft — turned out to be too tough to open under the unfortunate circumstances. The astronauts had struggled in vain to open the door during the fire, but the pressure inside the spacecraft sealed the door and made it impossible to open.

The board listed a damning set of circumstances, failures and recommendations for future spacecraft designers to consider.

The U.S. Senate conducted its own investigation and hearings and published recommendations of its own, while saying NASA's failure to report its problems with Apollo "was an unquestionably serious dereliction."

Several changes were made to the design of the Apollo spacecraft to improve crew safety. The flammable oxygen environment for ground tests was replaced with a nitrogen-oxygen mix. Flammable items were removed. A new respect developed between the astronauts and the contractors concerning design changes, which were implemented more effectively. Most notably, the door was completely redesigned so that it would open in mere seconds when the crew needed to get out in a hurry. [Photos: The Apollo 1 Fire]

Decades later, NASA recalls the Apollo 1 incident every January in an annual Day of Remembrance. It also honors the Challenger and Columbia crews, who died in 1986 and 2003, respectively. Further, an exhibit honoring the Apollo 1 crew was opened at the Kennedy Space Center in 2017, displaying the hatches that were on the spacecraft. The exhibit was done in consultation with the astronauts' families.

Additional resources:

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022 covering diversity, education and gaming as well. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before joining full-time. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House and Office of the Vice-President of the United States, an exclusive conversation with aspiring space tourist (and NSYNC bassist) Lance Bass, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?", is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams. Elizabeth holds a Ph.D. and M.Sc. in Space Studies from the University of North Dakota, a Bachelor of Journalism from Canada's Carleton University and a Bachelor of History from Canada's Athabasca University. Elizabeth is also a post-secondary instructor in communications and science at several institutions since 2015; her experience includes developing and teaching an astronomy course at Canada's Algonquin College (with Indigenous content as well) to more than 1,000 students since 2020. Elizabeth first got interested in space after watching the movie Apollo 13 in 1996, and still wants to be an astronaut someday. Mastodon: https://qoto.org/@howellspace