A huge ocean of liquid water may indeed slosh about beneath the frigid surface of Saturn's moon Titan, according to new evidence collected by a NASA spacecraft.

The observations were made by NASA's Cassini probe, which has been eyeing Saturn and its rings and moons from orbit since arriving at the gas giant in 2004.

Certain details of Titan's orbit and rotation aren't compatible with the behavior of a celestial body that is completely solid all the way through. But these details make a lot of sense if the huge moon is assumed to have a subsurface ocean, likely of liquid water, researchers said.

The new study is not the first to suggest Titan may have an underground ocean. But it adds another line of evidence in support of this supposition, which could make the intriguing moon a likelier candidate to support life as we know it.

"We think that the presence of an internal ocean is likely," said study lead author Rose-Marie Baland of the Royal Observatory of Belgium in Brussels. [Photos: The Rings and Moons of Saturn]

Explaining Titan's orbit and rotation

Titan, the largest of Saturn's more than 60 known moons, is considered one of the leading candidates to host life beyond Earth.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

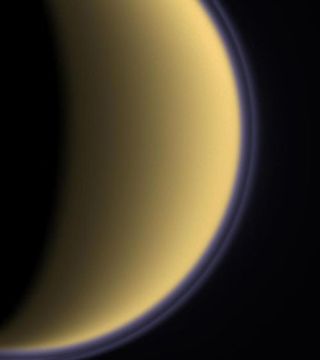

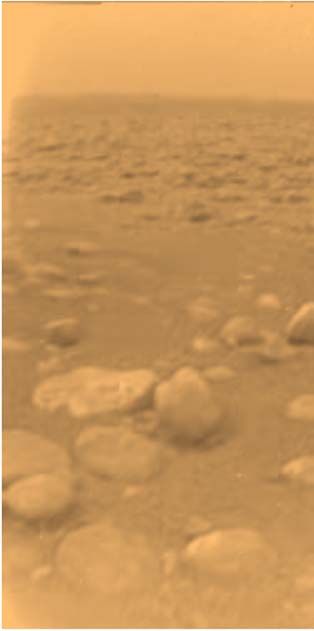

While its surface temperatures hover around a frosty minus 290 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 179 degrees Celsius), Titan boasts a thick, nitrogen-rich atmosphere in which thousands of different types of organic molecules swirl about. The moon also has a weather cycle based on methane, with methane rain pooling in liquid hydrocarbon lakes.

Other researchers had used Cassini measurements to discover a few key facts about Titan's rotation and orbit. They determined, for example, that the moon tilts by about 0.3 degrees on its axis of rotation (for comparison, Earth tilts by about 23 degrees). They also calculated Titan's moment of inertia, a term that describes how much a body resists changes to its rotation.

Several previous studies had concluded that Titan's tilt and moment of inertia don't make much sense if the moon is a completely solid body -- but that the numbers could work out if the moon has an underground ocean.

Baland and her team used these previous results as a jumping-off point for their study.

"We found this idea very interesting, and we have decided to go a little further," Baland told SPACE.com in an email interview.

A liquid ocean

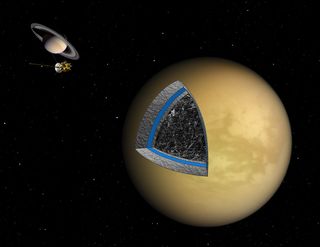

So Baland and her colleagues crunched Cassini's numbers in even greater detail. They found that Titan's orbital behavior indeed makes sense if the moon is assumed to have a solid interior surrounded by a liquid-water ocean, which itself sits beneath an icy "shell."

The sizes of these various layers are tough to pin down at the moment, but the researchers said their modeling work suggests the icy shell might be 93 to 124 miles (150 to 200 kilometers) thick and the ocean 3 to 264 miles (5 to 425 km) deep, with the solid interior making up the rest.

Titan is about 3,200 miles (5,150 km) in diameter.

Current thinking about Titan's formation and evolution suggests that this ocean would be composed primarily of water -- perhaps with a dash of ammonia -- rather than hydrocarbons or some other substance, Baland said.

If this were the case, Titan would join several other frigid moons in the outer solar system -- such as Saturn's moon Enceladus and Jupiter's Europa -- in the water-ocean club.

Other lines of evidence point to this same conclusion. The entire surface of Titan, for example, appears to be sliding around, suggesting that the moon's crust and core are separated by a layer of liquid water. Models of Titan's internal heat flow support this idea as well.

Baland and her team will report their results in an upcoming issue of the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

A candidate for life?

Some astrobiologists speculate that some exotic type of methane-based life could be swimming about in Titan's hydrocarbon lakes. [5 Bold Claims of Alien Life]

But the only life we are certain of is here on Earth. And on our planet, life is tightly tied to liquid water; pretty much anywhere the stuff is found, life takes root and sticks around. So the presence of liquid water on Titan would make that already intriguing world an even better candidate for life, researchers said.

"Astrobiologists do not not really know yet what are the necessary conditions for life to emerge, but it seems that the presence of water is a requirement," Baland said.

The researchers hope the new study will inspire others to keep probing Titan's depths until the question of Titan's subsurface sea is settled once and for all.

"We hope that it will encourage other scientists to look for any other evidence for this ocean," Baland said.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.